By Bruce and Athena (Teena) Tainio

Charles Walters, as quoted in Secrets of the Soil, by Peter Tompkins and Christopher Bird, says of microbial life: “There are more kinds and numbers of minute livestock hidden in the shallows and depths of an acre of soil than ever walk the surface of that field.”

As much as a cattle rancher’s livelihood depends on healthy livestock, he and his cattle’s very lives depend on armies of beneficial microbes for survival. Microbes are the foundation for all life on earth; without them the earth would be nothing more than a barren rock. There would be no fertile soils, no plants, no trees, no insects, no animals and no humans.

Soil bacteria secrete acids that break down rocks, and enzymes that break down dead plant and animal matter into rich, life-giving soil, while transforming minerals into forms that are usable to plants. Microbes help prevent soil erosion, combat disease organisms that attack plants, animals and humans, and are an important link our food chain.

Like any livestock, microbes need proper food and shelter to grow and thrive. Composting is an easy way to provide a suitable environment for raising your own “herd” of beneficial microbes and ultimately build nutrient-dense, energy-packed soil for your farm or garden. All that’s required are a few basic ingredients, a little space, a good nose, and a little know-how.

Compost provides a sustainable environment for beneficial soil microbes.

Compost provides a sustainable environment for beneficial soil microbes.

Composting Ingredients

Before starting the composting process, it is important to know how to blend the right materials to provide a balanced food supply for your digester microbes. No single material is sufficient by itself to create good compost. The two main elements essential to compost are nitrogen and carbon.

Nitrogen is the essential building block of proteins for microbial growth and reproduction. A shortage of nitrogen-rich materials causes slow growth rates of the microorganisms, which slows down decomposition. Carbohydrates (sugars) are required for energy (heat) and a source of carbon for microbial cellular protoplasm.

Creating a nutrient-balanced compost requires a wide variety of materials. Some plants contain substances that enhance beneficial microbial activity, while others are accumulators of specific minerals and trace elements.

In general, weeds are more likely to provide better nutrient balance than most cultured crops. For example, certain types of vetch are selenium accumulators. Comfrey and lamb’s quarter provide manganese, and dandelion is high in potassium (see Table 1). Yarrow, one of our favorites, carries more than 6,000 species of microbes on its leaves and makes an excellent microbial inoculant as well as an overall source of nutrients and complex amino acids.

Crushed eggshells are a good nonplant source of calcium. Just rinse, dry and grind them in a blender or food processor before adding to the compost pile. And here’s a great idea from the owner of our local health food store: instead of throwing away outdated vitamin and mineral supplements, grind them up and add them to the compost pile. The rule of thumb here is, the more variety of materials you have, the better your mineral balance is likely to be.

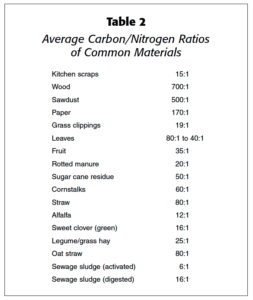

Ideally, the carbon-to-nitrogen ratios of a successful compost program should be 30 to 1. The precise amounts of carbon and nitrogen are difficult to ascertain, but knowing proper ratios is not so important as long as the compost is working well and remains warm. As a general rule, use two-thirds high carbohydrate matter, such as dry leaves, stems, straw, shredded paper, etc., to one-third green, succulent material high in nitrogen content, such as fresh grass clippings or weeds. See Table 2 for some carbon/nitrogen ratios of commonly used materials. Because microbes are the work force behind the transformation of waste materials into a usable soil amendment, one needs to ensure that a good variety of digester microbes go into the mix. Besides the traditional shovel or two of rotted livestock manure or garden soil to start microbial action, it is possible to achieve a faster and surer response by adding a multiple-strain microbial digester product (such as Tainio Technology’s Herman III).

By using digester microbes, creating the right C/N ratio and maintaining proper aeration, it is possible to produce finished compost in as little as 12 to 14 days.

Know Your Local Soil

Many regions are historically deficient in certain minerals. Here in eastern Washington, the soil is typically deficient in selenium, so even if we use vetch — a selenium accumulator — as one of our ingredients, our compost will still most likely be deficient in this important trace mineral.

The addition of a broad-spectrum mineral source such as rock powder or seaweed is good insurance against any possible nutrient deficiencies when building compost.

This simple addition may have saved an organic fresh-market vegetable farmer who contacted us several years ago, desperately seeking help for his failing crops. An Extension agent from the local university had diagnosed his problem as some unknown virus, and not being a regular client of ours, he had no soil test to give us any clues. What Bruce Tainio found when he arrived at the farm was not a virus, but a crop of nearly dead plants with all of the classic symptoms of manganese deficiency, which was later confirmed by a tissue test.

The farmer couldn’t believe it was possible to have a deficiency in his soil because, he explained, he used the best organic materials he could find in his composting program — manure from the dairy down the road and a variety of straw from a neighboring grain grower.

With all of that, how could his soil be deficient in manganese? Tainio explained that the soils in and around this coastal farm community were typically deficient in manganese, and therefore any local materials he used for compost would not supply him with adequate supplies.

Unfortunately, at that time the organic certification program was still in its infancy, and supplement choices were very limited, and so this farmer’s crop could not be helped in time. The few sick and nutritionally deficient vegetables that survived were harvested and sent to market, where the consumer paid premium prices for what they assumed to be healthy food.

A happier story concerns the Findhorn Garden community founded in the 1970s, and how a free and abundant supply of seaweed from a nearby beach was instrumental in turning a wind-blown patch of sand where nothing would grow into a rich and productive Garden of Eden. Perhaps if the farmer with manganese problems had known of and taken inspiration from the story of the legendary Findhorn Garden, his own story might have turned out differently.

The moral is to know your own region’s soils when planning your composting strategy — and to get a soil analysis!

Building and Managing Compost

With these facts in mind, then, let’s look at a basic approach to an effective composting program.

First, once you have collected your ingredients, chop or shred your materials as much as possible. All places in the stems, skins or leaves that have exposed or open areas are places that provide entry points for the digester microbes, so the finer the material, the faster the digestion process.

The largest pieces of stem and stalk will be the slowest to decay. Mix the chopped materials uniformly.

One important key to successful composting is moisture. The material should be moist but not soggy. Green materials usually provide all or most of the moisture the compost needs. Turning will cause much of the moisture to steam off, so in dry weather it may be necessary to add some water. Remember, however, that excessive water can drive oxygen out of your compost, leach nutrients, and lower the temperature — so water sparingly and only when necessary.

Other important elements for rapid composting are frequent aeration and appropriate temperatures.

The first turning should be made on the second day after the compost is built; again on the fifth day, then again on the seventh day and once more on the eleventh day.

During the process, monitor the temperature of your compost daily. Ideally it should range between 140°F and 160°F. If it gets too hot, turn the pile more often. If it isn’t reaching optimum temperature, add more nitrogen material.

After the last turning, the temperature of the compost should begin to drop down to about 110°F. At this point your compost should be finished and ready to apply. Fresh compost is rich with living energy and should be used quickly. If it is left to age in the pile, the microbe population will gradually dwindle or turn anaerobic. To revive compost that has been stored too long, just mix in a little microbe digester product before you apply it. (A good idea when using commercial, bagged compost, too, whether for soil application or tea brewing.)

Tips for Checking Compost Quality

You can use your nose to monitor and diagnose the state of your compost.

For example, having excessive amounts of nitrogen materials causes an excess of ammonia-smelling gas to be released when the compost is turned. If this happens, just add more carbohydrate material to correct the balance. Keep in mind, however, that it is better to add too much nitrogen-rich material than to not have enough to heat the decomposing matter.

Heat is needed to augment microbial activity as well as to kill weed seeds, parasites and pathogens, and to digest any toxic chemicals. This became a problem a few years ago for a large commercial composting operation in our area. When people’s tomatoes began to die, they traced the culprit back to an herbicide commonly used on lawns and brought in on grass clippings. The composting plant had failed to provide the right combinations of elements to ensure proper temperatures and microbial numbers.

The objective is to promote aerobic (oxygen-rich) digestion of your materials. If you fail to turn your compost enough or it becomes too wet or too compacted, the microbes can turn anaerobic (without oxygen) and create a sulfur or rotten egg smell.

Let your nose be your guide: finished compost should have a sweet, earthy smell.

Composting Tips for Livestock Waste

If you are fortunate enough to have horses, goats or rabbits, you have the ingredients for another type of compost.

All you need in addition to barn waste is a good digester microbe product and some patience. We have two miniature horses that provide us with plenty of manure, an occasional bale of moldy hay, and some bedding chips. Every few months we just sprinkle some microbes over the manure pile and keep layering on more barn waste. Microbes and worms continually digest the waste, so that the size of the pile never becomes too unmanageable. (Digester microbes and enzymes mixed together and sprayed around the barnyard work well for controlling fly-attracting odors, too.)

Every year or two, we push back the newest top layers (14 to 16 inches) to find a cache of rich, sweet-smelling compost with an amazing capacity to hold moisture; a much-appreciated bonus in our semi-arid climate. Added benefits that come with our manure compost are the huge colonies of red worms and beneficial fungi that have taken up housekeeping there.

This no-fuss method of composting works well with horse manure because horses have relatively inefficient digestive systems, which means the manure contains high levels of partially digested carbohydrates and lower levels of nitrogen.

The C/N ratio is about 20:1, and with the addition of a little bedding and hay waste, the ratio is excellent for composting. In addition, the round, compact shape of the manure creates spaces for air circulation in the pile. It is important on food crops to use manure only if it is well-aged and composted to insure against possible parasite contamination. Composting time will also allow for microbial remediation of any residual chemicals such as de-wormers.

Tips for Composting Field Stubble

Cornstalks or grain stubble left in the field after harvest can be composted where they stand. Disc or till so that the stalks are well chopped, then spray-apply a combination of enzymes and digester microbes.

By the following spring, most of the stubble will have been digested. Any remaining debris will shatter into fine particles when tilled, leaving the soil richer in available minerals and abundant microbial life.

Editor’s Note: This article was first published in the September 2007 issue of Acres U.S.A. magazine. For more information, visit www.tainio.com, or purchase their book, Farming in the Presence of Nature, from the Acres U.S.A. bookstore.